Brittany, cultural effervescence

A peninsula at the tip of Europe, Brittany is bordered to the north by the English Channel and to the south by the Atlantic Ocean. It is one of six Celtic nations and is the only one to be found on mainland Europe. From the 4th century, the Britons began to settle on the island.

The Breton flag, Gwenn ha du, which literally means “white and black” was created by the autonomist architect Morvan Marchal in 1923. It incorporates the “mouchtetures d’hermine”, the symbol of Breton sovereignty and the traditional colours since the 13th century. The number of bands symbolises the nine historic provinces that make up Brittany.

In the 9th century Brittany began to emancipate itself from its Carolingian neighbours. Nominoë, duke of Brittany and Erispoë, and his son, the king, expanded the territory and made it into the form it retains today. Torn between France and England, the Montfort dynasty (14th/15th centuries) managed to keep the country independent. It was then that Brittany saw its golden era, becoming an unchallenged maritime power. A kingdom then a duchy, Brittany was forced to unite with France by the union of its sovereignty in 1532. Having become a province, Brittany retains many privileges (specific legislation, tax collection).

During the French Revolution, it lost its rights and was reduced to 5 departments without identity. It wasn’t until the 19th century that the Breton cultural movement began to fight for its culture, its language and for self-determination.

It is only in the 1970s that the teaching of Breton began, which had long been despised by the authorities. During this period, armed activism by the Front for the Liberation of Brittany intensified (1963). Having acquired few rights, the Bretons fight continuously for the reunification of arbitrarily divided territory and for the Breton and Gallo languages, which are in danger of extinction today. Without autonomous status, Brittany does not have the means to manage issues of concern, in regards to economic, cultural and linguistic diversity.

Brief history

Like elsewhere in Europe, in the middle of the 19th century the Breton movement (Emsav) became aware of the cultural riches that exist in Brittany. Its leading figure is the Marquis T.-H. de la Villemarqué who collected folk songs, which he published under the name Barzaz Breizh. In the 1920s, an artistic movement was born, which included more than fifty artists in all fields (literature, music, visual arts, architecture). They were called Seizh Breur (Seven Brothers). Their goal was to combine tradition and modernity in art and give acclaim back to Brittany in a more militant way than their predecessors. By giving Bretons back a taste for their culture and languages, this movement has created a modern Breton, art-nouveau style, which can still be seen in contemporary design.

Identity card

| Name | Breizh | Breton Bertaèyn | Langue d’oïl Bretagne | French |

| Population | 4,713,813 inhab. (2017) |

| Area | 34,034 km² |

| Languages | Brezhoneg | Breton (without official status) Galo | Langue d’oïl ( without official status ) Français | French (official) |

| Number of native speakers | 225 000 | Breton (2018) |

| State of guardianship | France |

| Official status | Region without autonomous status in France |

| Capital | Naoned | Breton Nantes | French & Roazhon | Breton Rennes | French |

| Historic religion | Roman Catholic |

| Flag | Gwenn ha du | Breton (white and black) |

| Anthem | Bro Gozh ma zadoù | Breton (Old Land of My Fathers) |

| Motto | Potius mori quam foedari | Latin Kentoc’h mervel eget bezañ saotret | Breton (Death rather than staining) |

Timeline

- 4th–7th century • Bretons emigrate from the island of Brittany. They mingle with Celtic populations already present, while exercising political power.

- 9th century • Breton kingdoms unite under the authority of their sovereign, Nominoe.

- 14–15th century • War of succession sees the strengthening of the Monfort dynasty and the emancipation of Brittany.

- 1488 • The military defeats of the Duchy forces Brittany to join its neighbour, the kingdom of France.

- 15–17th century • The trade in cloth ushers in a Breton golden age.

- 1789 • Brittany loses all its rights under the Act of Union and begins a dark period, without a hold on its destiny. It no longer exists legally.

- 1941 • A “region” Brittany is created by the Vichy government led by Marshall Pétain, cutting off the Loire-Atlantique.

- 1970s • Emancipation thanks to the cultural movement. The Regional Council formally recognises Breton and Gallo as official languages of Brittany.

Geography

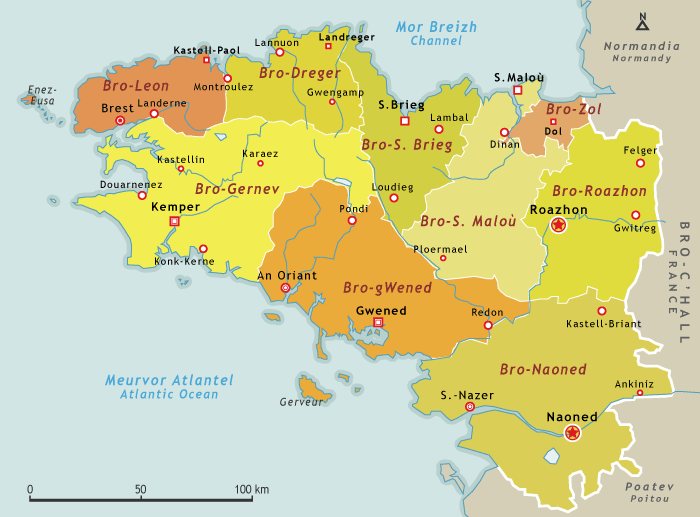

Brittany consists of nine historic provinces, original cultural entities maintaining a major cultural role known in Breton as “bro” (shown on map). Today, Brittany is made up of five departments, including the Loire-Atlantique, which was administratively separated under the collaborationist Pétain. Many islands surround it (Batz, Ouessant, Sein, Groix, Belle Isle, etc.). Normandy, Maine, Anjou and Poitou are found at its eastern border. The urban network comprises many cities, mainly located on the coast. To the east, Rennes, the administrative capital and Nantes, seat of the rulers, are the most emblematic and are considered the two historic capitals. To the west, Brest, a port city, has largely contributed to the reputation of Brittany as a great maritime nation. On account of its peripheral location at the edge of Europe, Brittany has suffered from a strong economic disadvantage, subsisting on agriculture and fishing. It began to develop upon the arrival of what is now called the “Breton model”, based on the consensus of economists and politicians, particularly the CELIB during the 1960s.

Language

Brezhoneg

The Breton language is a Celtic language of the Brythonic branch. Spoken since the 5th century, the Breton language is still specific to Brittany. It is practised by more than 225,000 people, essentially to the west of Brittany. It is also spoken in the large towns to the east of Brittany (Rennes, Nantes). There are four variations, between which mutual understanding is mostly possible, though it is more difficult with the people of the Vannes area. Other variants are commonly called Cornish, Leonard and Trégorois. Breton does not benefit from official status, as France rejects any recognition of linguistic minorities. However, the situation is changing slowly. For its part, Brittany officially recognised Breton and Gallo (Oïl language practised in the east of Brittany), but this recognition has only symbolic value. There are now over 16,500 students learning Breton (2002), which is low compared to the number of children enroled in schools. Breton, active in the field of information technology, remains fragile. Indeed, it is classified by UNESCO as an endangered language.

Politics now

The Breton administration has a Regional Council with no power to legislate. Despite the dynamic force of the Breton movement, it is mainly on cultural grounds that activists operate. However, Breton political parties always reinforce their positions. Indeed, the autonomist Breton Democratic Union has four regional advisers (between 2004 and 2009 the majority were Progressive Socialists / Greens). The Breton Party, in spite of its young age, has candidates in various elections and also has local officials. There are also some groups claiming federalism or anarchism. The extreme left is represented by a separatist party named the Breizhistance. The themes defended by the Breton parties are essentially the recognition of Breton people, the officialisation of the Breton language and the reunification of Breton territory into its historical configuration (the department of Loire-Atlantique is actually separated from the administrative region of Brittany despite polls indicating that 70% of the population desires reunification). In 2000, a CSA poll revealed that 23% of Bretons were strongly or somewhat in favour of independence.

The most representative autonomist or separatist Breton parties

- Unvaniezh demokratel Breizh / Breton Democratic Union (UDB) (Progressive Autonomist)

- Strollad Breizh / Breton Party (Separatist Social Democrat)

- Breizhistance / Brittany Socialist Party(Revolutionary Left)